The following is a presentation given at the 6th Annual "Bridging the Spectrum" Symposium, hosted by the Catholic University of America's Library and Information Science program. More information on the Symposium

here.

Abstract: A discovery service is a single and unified index of a library’s holdings across multiple

media. As more academic libraries are implementing a discovery service as the primary online face of the library, library websites have evolved with them. Website changes, however, are relatively unexamined. This briefing reports on one library’s experience with a discovery service, EBSCO’s EDS, and the effects of the discovery service on the library website. It compares these changes to those made by other academic libraries. It answers the question of whether there exists a set of best practices for academic library websites upon implementing discovery services, and addresses what happens to online public access catalogs (OPACs), individual databases, and other items frequently found on academic library websites. It also discusses how to market and promote website changes to academic communities.

What is Discovery?

It is not two French robots that play disco.

Single searching across databases, with results ranked by relevancy

- The ability to sort said results

- Full text

- Features for end users

Via Hoeppner, A. (2012) The Ins and Outs of Evaluating Web-Scale Discovery Services. Infortoday.com,

http://www.infotoday.com/cilmag/apr12/Hoeppner-Web-Scale-Discovery-Services.shtml Accessed 29 January 2014

Our library chose Ebsco's Discovery Service (EDS) in large part because we found it the "least bad." EDS' use of metadata to retrieve relevant results seems to be more robust than the other options we examined, Primo and Summon.

In addition, librarians judged the results returned by EDS superior to those returned by other discovery services, though

this study is not without its methodological issues.

“On the quantitative benchmarks measured by this study, the EBSCO Discovery Service tool outperformed the other search systems in almost every category.”

- Asher, Duke, and Wilson (2013) Paths of Discovery: Comparing the Search effectiveness of EBSCO Discovery Service, Summon, Google Scholar, and Conventional Library Resources. College & Research Libraries. 74(5) 464-488. http://crl.acrl.org/content/74/5/464.full.pdf+html

This is our first semester using a discovery service, so we're eager to see what happens.

Though people have many goals using discovery services (some more realistic than others), including promoting local collections, replacing Google as the primary place people do research, and expanding the universe of available resources, among others, our main goal is to reduce friction for people who use our library website.

With that in mind, here is our lovely library website. Keep in mind thanks to unfortunate protocols in academic information technology, we at the library are somewhat "locked in" to this format. We use WordPress throughout the university.

Please note our mission statement front and center, because of course when people go to a library website, that's among the first things they want to see.

When I see a mission statement on the front page I’m like

We have some "stuff" on the left-hand side of the page that is rather important. A goal is to get this stuff front and center.

Let's take a closer look.

Note that we're trying to use plain, natural language. Regrettably, at the moment we're not able to do that with our discovery search box, but we are very open to suggestions here.

Here's our current search box, along with another friction point that applies to off-campus users.

Here's what will replace it, the discovery search box.

Again, we're trying to take the stuff from the left-hand side, and put it front and center.

Here's our old online public access catalog (OPAC).

See, I made a meta-funny. Right now our community searches our catalog, doesn't find something, and then clicks on a link to search the catalog of the consortium we're partial members of (like Facebook says, "it's complicated.").

And here's what it's going to look like.

Note where our consortium is circled on the right. If you do a keyword search in our catalog, it will trigger a keyword search in the consortium catalog, displayed on the same page. If you search by author, that consortium widget will do an author search as well, and so on.

Our databases move from the left-hand side to the center.

As do our subject research guides, our in-house version of LibGuides.

We're trying to reduce friction here, get people where they want to go on our site, quicker.

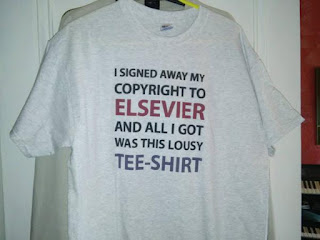

One of the things I'm most proud of about our move to discovery is the open access (OA) search feature.

That definition comes from the Budapest Initiative, by the way. I don't expect this feature to get much use, however, I do think its presence is important. I want it to jump-start conversations, to provoke thought around issues of access to information, academic publishing, and scholarly communication. In short, we want to create a discursive space for these issues.

Here's what the OA search output looks like.

Note not only the consortium widget, but also a Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) widget.

The OA search is the primary reason why we've taken so long in implementing discovery. We really wanted to push Ebsco, our vendor on this, and to their immense credit, they responded. I know that I'm sometimes guilty of painting the library-vendor relationship as adversarial, but that's not always, and even not often, the case. As far as I know our library is the only one out there to ask for this from a vendor, but there's no reason why your library can't do this, too. This is how collaboration is supposed to work.

As presently constructed, our library sits between full collection discovery and full library discovery. In the former, libraries use discovery services to promote their collections. In the latter, the discovery search not only encompasses collections, but also locally hosted items that are on the library website, but are not part of the collection. Think room reservation forms, requests for materials, and the like.

We're going to market discovery services in several ways, chief among them, perpetual beta.

We'll also use library instruction one-shot sessions to talk about discovery, as well as table toppers in the dining hall, and I'll make a few appearances there as well, armed with a computer and a projector to promote the services.

We're going to dive right in and make mistakes. We'll tinker with it, and solicit feedback. We may tweak the relevancy rankings to excludes newspaper articles and reviews... or we may not.

A current debate among proponents of discovery is how best to express search results.

Villanova, above, and North Carolina State University, below, both use what's termed a "bento box" model of search results output.

Note that the results are compartmentalized, broken down and presented using controlled vocabulary.

At present, we are not using bento. This is because our community is familiar with Ebsco's blended interface, in which the results are presented as a list, ranked by relevancy based on the available metadata. Moreover, bento, to me, looks a lot like Yahoo!'s hierarchical website organization structure, whereas the native Ebsco interface looks more like Google's. Rhetorical question: which of those won out? (Pause.) That's what I thought.

Discovery is not without its critics, and they are justified. They are aimed more at undergraduates than at faculty, graduate students, and librarians, so these three later groups may not like it as much, as they are more advanced searchers who will use individual databases to find what they want. With that in mind, we may not want to "throttle" results by filtering out things like newspaper articles and reviews, as those are important parts of the research process for undergraduates.

The metadata that Ebsco uses in its databases is privileged in its discovery service, so Ebsco resources are promoted, sometimes at the expense of a better resource from another, rival database.

We've asked Ebsco to play nicer with other vendors here, in terms of metadata integration, as Primo and Summon have, and there are

some encouraging signs.

One study found that a custom Ebsco search box, trawling only Ebsco databases, would be nearly as robust as EDS, again, because of how Ebsco's metadata brings their local results to the top.

Would an custom EBSCO search box do pretty much the same thing as EDS?

- Calvert, C. (2015) Maximizing academic library collections: measuring changes in use patterns owing to EBSCO Discovery Service. College & Research Libraries. Anticipated Publication Date: January 1, 2015. Manuscript#: crl13-557. Available from http://crl.acrl.org/content/early/2014/01/17/crl13-557.full.pdf

In some sense, are we just spending money for the sake of spending money? It's a cynical question, but a valid one all the same. Often times we librarians don't get an increase in funding unless we ask for something shiny and new that will improve our communities, as opposed to increasing funding for existing initiatives. In this sense, it almost doesn't matter whether discovery works or not, because it represents a semi-permanent budget increase.

In sum:

Be empathetic

- Use the language of the user

- Reduce friction

Clear goals and outcomes

- work toward them, or

- backwards from them.

Is your goal to improve the user experience, to promote your holdings and databases, to expand the searchable universe...? Different goals require different strategies and tactics.

Mistakes are okay

- If you fix them quickly

- We are in an academic library, not dealing with nuclear launch codes. The far majority of mistakes one might make can be easily corrected and fixed.

And that, my friends, is the end of the presentation. Thank you.

Two very useful sites on discovery services:

Aaron Tay,

Musings About Librarianship and

Unified Resource Discovery Comparison.

Related, on this site:

On Failure: "Elizabethtown: Embedded Librarianship as Overreach."

A Rant on Library-Vendor Relations

Copyright for Educators

A Modest Defense of QR Codes in the Library

UPDATE, July 8th post:

More Thoughts on Discovery, Plus a Poster

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)