|

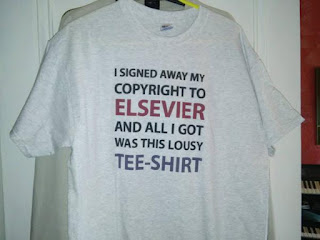

| Yet again, http://www.cafepress.com/fakeelsevier |

Johan Rooryck, executive editor of the journal until his resignation takes effect at the end of the year, said in an interview that when he started his editorship in 1998, "I could have told you to the cent what the journal cost," and that it was much more affordable. Now, he said, single subscriptions are so expensive that it is "unsustainable" for many libraries to subscribe. Rooryck is professor of French linguistics at Leiden University, in the Netherlands, where academic and government leaders have been sharply critical of journal prices.This was not the first instance of a journal editorial board quitting over Elsevier, as The Economist noted in 2012:

In 2006, for example, the entire editorial board of Topology, a mathematics journal published by Elsevier, resigned, citing similar worries about high prices choking off access. And the board of K-theory, a maths journal owned by Springer, a German publishing firm, quit in 2007.Simmons hosts a comprehensive list of journals that have declared independence.

Tom Reller, Vice President and Head of Global Corporate Relations at Elsevier, addressed this most recent resignation in a blog post. In it, Reller makes a number of claims that should go fact-checked. I do so below.

I am not the first person to parse Elsevier's statement. Martin Eve, Senior Lecturer in Literature, Technology and Publishing at the University of London and head of the Open Library of Humanities, which will play host to the new journal to be run by the previous editors of Lingua, Glossa, does an excellent job clarifying some of what Reller wrote. Eve notes that it was not Rooryck, solo, who wanted to take ownership of the journal, as Reller asserts, but rather the editors, writ large, and counters Reller's claim that Elsevier founded the journal. More importantly, Eve takes issue with Reller's definition of "sustainable," given that Elsevier reported a 37% operating profit in 2014.

|

| These are the 2012 numbers. Chart via Alex Holcombe at the above link. |

To Eve, let me add:

- In Reller's response, he notes that Elsevier is "the world’s third largest open access publisher," but this, too is misleading. His company is the largest publisher of scholarly journals, but of the 2,500 journals they publish, only 300 are fully open access. Another 1,600, including Lingua, have some hybrid form of open access. Elsevier's claim comes from its size, a function of how many journals it publishes. Elsevier is not a member of the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association, as some of its competitors are, including Springer, Wiley, Taylor and Francis, SAGE Publications, and Oxford and Cambridge University Presses, among others, which signals a lack of commitment to Open Access Gold, immediate free and open dissemination. Indeed, if one were to point to the largest strictly open access publishers, it would include the Public Library of Science and BioMed Central Ltd., owned by Springer, among others. Not Elsevier.

- Reller claims that "Elsevier will receive 1.2 million article submissions this year, publish 400,000 of them into a database of 12 million articles," for an acceptance rate of 33%, higher than that of the American Psychological Association, and many other publishers.* One effect of "the big deal" for libraries includes charging for lesser journals that don't get much use, similar to paying for cable television for just a few of the hundreds of available channels.

- To wit, the Massachusetts Institute for Technology notes that "UC economist Ted Bergstrom concludes through his calculations (including price per citation) that 59% of Elsevier titles are considered a “bad value.” In comparison, The American Physical Society has 0 titles that are “bad value” based on the same calculations."

- Elsevier is more than entitled to make a profit, which includes happy and productive employees that can exercise on the job, but sustainability is a two-way street. There are ways to make money in strictly open access environments that academic librarians should invite them to explore, such as "generating better metadata for... open access items; designing stronger, more relevant search functionalities; and creating attractive and user-friendly platforms." (Source)

- Per usual, when discussing issues of open access, faculty are barely present. So long as faculty cannot or do not or refuse to recognize the political economy of scholarly communication, the longer it will remain a moral hazard in which they are immune to its costs. If it is professionally and personally possible, academic librarians should initiate these conversations with faculty and academic administration. That means you, tenured librarians. To colleges and universities that employ scholarly communications librarians and help them succeed: thank you.

A Chronicle of Higher Education article on Lingua.

* Yes, I know that this is a problematic argument for a variety of reasons and I lack access to Cabell's Directory of Publishing Opportunities at the moment, but bear with me.